Indigenous Development versus Eastern Influence

Based on the paper presented by Sanford Holst at California State University, Long Beach on June 24, 2006

Identifying the origin of the beautiful Minoan civilization on Crete is a matter of some importance since—together with the Mycenaeans of the mainland—the Minoans are believed to have been the forerunners of classical Greece,[i] the widely-accepted main source of Western civilization.[ii] As we shall see, two distinct views on the possible origin of the Minoans continue to divide scholars, even to the present day: indigenous development versus Eastern influence. New evidence having a direct bearing on this issue is presented here, and a possible answer to their origin is identified.

To see this issue clearly, we focus on the Minoan palace society which existed on Crete during the period designated MM IB to LM IB (roughly 1950 BC to 1450 BC),[iii] and on the years which preceded it.

Minoans Background

With regard to the origin and rise of Minoan people, the ‘Eastern influence’ view was the first to arise. It came into being shortly after Sir Arthur Evans discovered the Minoan palace at Knossos on Crete in 1900 AD. Aspects of the architecture and artifacts seemed to reflect Eastern Mediterranean precedents, so Phoenician, Egyptian and other influences were suggested.[iv]

However a pivotal change occurred in 1972 when Colin Renfrew produced The Emergence of Civilisation with a completely different explanation: indigenous development.[v] This view held that the people of Crete evolved essentially in isolation on their island, and gave rise to all the grand elements of Minoan palace culture by themselves. Supported by most classical Greek scholars, this became the dominant view, and has kept that position to the present day.[vi]

In 1987 Martin Bernal produced Black Athena and entered the fray by raising two thought-provoking points.[vii] The first was that, from approximately 1785 AD onwards, historians re-drew the roots of Western civilization to exclude contributions made by Phoenicians, Egyptians and other non-Europeans. The second suggested this exclusion was heavily influenced by bias against Black and Semitic people. Though these produced outcries focused on ‘Afro-centrism’ and the like,[viii] most scholars today concede that some degree of bias seems to have occurred.

It is noted that the ‘indigenous’ argument allows Phoenicians and Egyptians to be excluded from any meaningful role in the rise of early Greek civilization. It hands the field-of-play exclusively to dwellers of the Greek mainland and islands. Many highly regarded scholars have weighed in on both sides of this issue, and I now introduce some additional clarifying archaeological findings. Together, all these sources form a broad and solid basis for resolution of this issue.

To digress for a moment. . . .

If you would like to discover more about the Minoans and Phoenicians than what is covered in this article, the book Phoenicians: Lebanon’s Epic Heritage is recommended. It is deeply researched but also a highly readable exploration.

Going beyond the few traditionally-cited facts, this authoritative work also draws from interviews with leading archaeologists and historians on-site in the lands and islands where the Phoenicians lived and left clues regarding their secretive society.

You can take a look inside the book. See the first pages here.

We begin our examination of this evidence by noting that both sides in the ‘rise of the Minoans’ argument agree on the following points: At the end of the fourth millennium BC, Crete was a rural agricultural society, whose people existed on self-sufficient, subsistence farming.[ix] Minimal, if any, trade took place, mainly confined to what one family might exchange with its neighbor. Yet by the early second millennium BC an incredible transformation had taken place. Crete stood as a marvelously complex society with vast palaces, centralized authority, highly skilled craft specialization, heavy traffic in import and export of trade goods, and a complex writing system employed by a central administrative bureaucracy. The issue which divides the two sides in this debate is: how did this almost miraculous transformation take place?

Indigenous Development

Colin Renfrew’s proposed model for indigenous development stated that, around the end of the fourth millennium, the subsistence farmers expanded from being primarily wheat-growers to also being cultivators of olives and grapes. Since olives and grapes could be grown on hillsides and did not require the flat land already being used by wheat farmers, the additional productive land might have allowed the population to increase. Then ‘redistributive chiefs’ could have arisen who administered and controlled the exchange of goods between the different farmers, each of whom produced only one of the three crops. To do this, the chiefs might have built large redistribution buildings to hold the agricultural produce until it could be distributed. After that, the chiefs could have encouraged people to specialize in various crafts to produce valuable goods for export, which would have increased the interdependence of craftsmen and farmers.[x]

This was an intriguing and imaginative model. Unfortunately, no evidence was found to show olive and grape production existed to any significant extent in Crete at this early date.[xi] That turned out to be a critical flaw which could not be overcome. In addition, the traditional response of small farmers to the introduction of additional crops was to diversify their crops, rather than to specialize and become vulnerable to conditions which might cause one crop to fail. Also, the possibility that chiefs would arbitrarily decide to redistribute crops for benevolent reasons seemed to run counter to historical human behavior.

In 1979 Clive Gamble offered a modification to cure one of these visible weaknesses. He suggested the governing leaders may have been forceful and demanding rather than operating for benevolent reasons.[xii] But the other failures of the model were still present.

In 1981 Paul Halstead suggested a different modification, offering that perhaps erratic weather patterns led to occasional crop failures. This might have caused farmers to voluntarily put surpluses into warehouses in good times, and draw them out when times were difficult.[xiii] The main problem with this suggestion was that other societies which followed this practice stored surplus grain in neighborhood granaries.[xiv] Grain was not normally hauled long distances to a massive regional facility. And it did not become a trade good, since farmers would have drawn out what they put in. This was not a fruitful explanation.

However, also in 1981, Tjeerd van Andel and Curtis Runnels proposed a more promising possibility. They expanded upon one of the alternatives mentioned in passing by Renfrew: trade and craft specialization might have stimulated this growth on Crete.[xv] For this they developed an elaborate mechanism of occurrences and developments which might have led to this trade having sprung up between Crete, the Aegean islands, and the mainland. However the chronology which was offered, and the delicate dependence of one event upon another, made it difficult to imagine this could have happened. A more critical problem was that the model could not explain why palaces did not spring up all around the Aegean, but only occurred on Crete.

Eastern Influence

Aside from the difficulties noted above, perhaps the most debilitating problem in the indigenous view was that it finally had to admit trade in one form or another was essential to this growth on Crete. Trade brings some degree of influence, whether it be small or large. We are all aware of countless examples where peoples received, for the first time, bronze weapons, a potter’s wheel, and many other materials through trade which had a profound effect on their society. But rather than speak in generalities, let us consider what happened on Crete.

Was there trade between the people of Crete and off-island peoples during the long development period leading up to the first Minoan palaces?

Egyptian stone bowls were found at Knossos which date from around the beginning of the third millennium. Incised Ware pottery from the islands of the central Aegean were also found from this time period.[xvi]

At the midpoint of this millennium, marble figurines of the folded-arm type were being imported from the Cyclades islands. Bronze daggers were found in tombs from this period, even though Crete was not known to have developed any local sources of copper at that time. Local people were believed to have imported this essential metal from the Aegean island of Kythnos.[xvii] Urfirnis sauceboats from mainland Greece dating from this period were found at Knossos. Ivory from the Levant was being used to make Cretan seals at this time.[xviii]

Six Egyptian scarabs were found in tombs dating from the end of the third millennium in the Mesara plain of Crete.[xix]

By the beginning of the second millennium, imported pottery from the eastern Peloponnese was common. Pottery from the Dodecanese islands and the coast of Western Anatolia also dated from this time. Fragments of pottery from Crete were found in contexts of this period in the Levant, Cyprus and Egypt.[xx] Trade clearly moved into high gear during this time when the first Minoan palaces were being built.

Without question, there was outside trade throughout this long development period up to and including the building of the first Minoan palaces. And this trade was not limited to islands close to Crete, but extended far to the east. Given this trade, we see a much more powerful and natural driver for development than the benevolent ‘redistributive centers’ and other offerings of the indigenous view. The simple fact that trade begets development would be amply demonstrated again in the Aegean a thousand years later, when it contributed strongly to the growth of Greek city-states and the flowering of classical Greek society.

Do we see specific examples of trade bringing outside influences into Minoan society?

Even Renfrew tacitly acknowledged that, in the third millennium BC, flax—and the making of linen from flax—appears to have been brought to the Aegean from the Near East[xxi]. At that same time, a new style of pottery known as Agios Onouphrios began to be produced in many parts of Crete. This style of red-on-buff pottery was clearly identified by Keith Branigan as having been borrowed from the area he identified as Syria-Palestine, where it had existed ever since the fourth millennium BC.[xxii]

Saul Weinburg likewise pointed out many similarities between the Cretan culture in the third millennium BC and the slightly earlier Ghassul culture in Palestine. These included “bird vases, mat impressions on the base of pots, high pedestal feet for chalices, suspension lugs, clay ladles, pattern burnishes, cheese pots, impressed spirals, contracted burial in cist graves, pithos burial, pyxides and incised decoration.”[xxiii],[xxiv] Branigan agreed and expanded upon these similarities. He further stated the belief that these influences had come up to ‘Syria’ before being conveyed to Crete.[xxv]

It should be noted that a number of historians subscribe to the imprecise practice of interchangeably using the names Syria, Phoenicia, Canaan or Palestine. This practice has led to confusion regarding the actual history of each of these entities. The country of Syria did not exist in 2000 BC, nor did Palestine. Recent research has shown the Phoenician land and society had diverged from the Canaanite land and society by 3200 BC.[xxvi] Phoenicia, the proper designation for the home of the Phoenicians, was located—to greater or lesser extent during the years involved—in the land known today as Lebanon. It was surrounded on three sides by Canaan, and on the fourth by the Mediterranean Sea. Additional details of Phoenician history are deferred until later in this paper.

Branigan reported that during EM III (ca. 2300 – 2100 BC) Cretan metallurgy was “considerably influenced by types and techniques used in Syria and Cilicia and in this and the following period there are some actual imports of Syrian daggers.”[xxvii]

Another of the outside influences which came to Crete at this time was the peacefulness exhibited in Minoan society. Excavations have revealed fortification walls once existed at a number of locations in the latter part of the third millennium, including Knossos, Malia and Kouphota. All of these walls seem to have been completely abandoned just after the first palaces were built.[xxviii] In addition, the finding of any weapons on Crete was quite rare during the Minoan palace period. This was highlighted by the discovery of ceremonial weapons at Malia dating from the early palace years. Note also that the ‘double-axe’ was used symbolically throughout the palace era. These finds suggest the use of weapons had previously been more common in the land before the palace period, and was being commemorated in old rites and symbols brought into the relatively weaponless palace society. In all these things we see a culture that became distinctly more peaceful with the arrival of influences which led to Minoan palace society.

A further change in Minoan culture introduced at this time was the adoption of Egyptian-style burials and funerary customs. We began to see clay coffins being used, along with Egyptian funeral paraphernalia: stone palettes, sistrum (for music), alabastra, cylindrical vessels, goblets, miniature amphoras, ceremonial shells, and clay models of bread loaves.[xxix]

Renfrew postulated a smooth, continuous rise in indigenous development at Crete. However scholars now note, as John Cherry put it, “the transition to palace society in the centuries on either side of 2000 BC was in several important respects a quantum leap beyond anything that had gone before.”[xxx]

During the years following 2000 BC, as Bernal described it, Crete “changed from a prosperous and cultivated society of small communities into a group of centralized states ruled from palaces.”[xxxi] He added, “There is no doubt that the building of the Cretan palaces around 2000 BC represented an extension to the Southern Aegean of an economic and social system that had been established over much of the Middle East for over a millennium.”[xxxii]

L. Vance Watrous pointed out, “In MM I (ca. 2100 – 1800 BC), a number of new vase shapes, which include the goblet, carinated cup, conical cup, fluted kantharos, and theriomorphic rhyta, appear on Crete in imitation of Near Eastern vessels with a long prior history.”[xxxiii]

James Walter Graham studied the palaces of Crete for most of his life. He clearly noted:

“That resemblances do exist between the Cretan and Near Eastern palaces in some respects can scarcely be denied, and likewise . . . between Cretan and Egyptian architecture.” These resemblances included the fact that “rooms are arranged around courts; different quarters of the palaces are used for different purposes . . . there are bathrooms with clay bathtubs, audience halls; and so on.” He continued, “The available evidence suggests, to my mind, that when the palaces first came into being around 2000 BC the Cretan architects, though aware in a general way of palace architecture elsewhere, created forms suited to, and determined by, Cretan needs and the Cretan environment, and employed constructional techniques traditional to the eastern Mediterranean and with which they were already in general familiar. . . .

[They] developed more efficient and more peculiarly local forms, forms which were in some measure affected by the architecture of their overseas neighbors. . . . for new decorative forms they turned especially to Egypt. . . . The possible adoption of the Egyptian type of banquet hall when Minoan kings wished, in imitation of the pharaohs, to add this luxury feature, would fall in the same category.”[xxxiv]

James Walter Graham

We see, therefore, Crete clearly received outside influences. Let us look beyond this finding, and see if we can determine the major source of these influences.

New Facts

To locate the primary source or sources of outside influences on Crete during this formative time, we must look at the wider context in which this Minoan society arose.

What was happening in the Mediterranean during the third and second millennia BC which could have a bearing on these events in Crete?

At Hierakonpolis in Egypt, Michael Hoffman’s excavations documented the products of Phoenician trade with the Egyptians were much in evidence by 3200 BC—in this case, the products were massive pieces of cedar of Lebanon.[xxxv] It goes without saying that Egypt was much more populous than Byblos, the only Phoenician city in Lebanon at that time. To support their Egyptian trade, the Phoenicians had little choice but to seek more sources of raw materials from lands to the north and west. From the beginning of the third millennium onward, this Phoenician-trade influence can be seen in the Aegean, where the primary commerce shifted from wheat fields in northern Greece to new trade-based commerce in the south.[xxxvi]

French archaeologist Maurice Dunand demonstrated a small town existed at Byblos from at least 4500 BC, and it became a walled city after 3200 BC. Classical historian Herodotus[xxxvii] and modern-day archaeologist Patricia Bikai[xxxviii] clearly showed that the Phoenicians established the city of Tyre south of Byblos circa 2750 BC. Tradition held that the neighboring city of Sidon was founded at this same time. In fact, recent excavation work sponsored by the British Museum confirmed Sidon existed in the third millennium.[xxxix] It is well established that the Phoenicians were peaceful people, experienced in ship-building, who raised large buildings and walls with ashlar-cut stone, and dominated sea trade in the Mediterranean by 2500 BC.[xl] Their trading house was seen to be their administrative center and the residence of their civic leader,[xli] who came to bear the title of ‘king.’ At Byblos a large building has been unearthed from this time period which is believed to be the earliest Phoenician trading house and adjacent warehouse. Among the Phoenician society’s established characteristics, seen many times over the centuries, was the serious desire to blend in, and the propensity to adopt cultural elements from those with whom they traded. They borrowed especially heavily from the Egyptians, their major customer.[xlii]

It is noted that Black Athena documented in considerable detail the exclusion of Phoenicians and Egyptians from modern histories. One of the residual effects of this exclusion has been that today’s texts simply state the Phoenicians are a ‘mystery.’[xliii] That declaration presumably justified why no further history was offered with respect to these people. Yet in reality, a tremendous amount of information about the Phoenicians is found throughout the classical sources, including Herodotus, Thucydides and others. There is also extensively-detailed data from archaeological reports by Hoffman, Bikai and others. There is more than enough information to write a complete history of the Phoenician people. Surprisingly, this complete history—from 3200 BC to 146 BC—was only told for the first time in Phoenicians: Lebanon’s Epic Heritage (2005).[xliv] In this source one sees such a wealth of classical and archaeological information that it becomes impossible to go back to the belief that the Phoenicians are a ‘mystery.’

In events which would have a serious impact on Crete, we see—late in the third millennium—how fierce Amorite tribes descended into the land beside the Phoenicians in Lebanon and caused a major change. Those raiders twice sacked Byblos,[xlv] the leading city of the Phoenicians, and forced action to be taken. Archaeologist Bikai, working at Tyre, discovered habitation ceased to exist in the excavated area of that city beginning circa 2000 BC.[xlvi] There was only a deep layer of sand which accumulated atop the previous buildings and pottery. Similarly at Sidon, the British Museum team found a deep layer of sand beginning at this same time.[xlvii] Dunand told us Byblos was downgraded during this period as well.[xlviii] Where did all those people go?

Given the current discussion, one notices this was the same time period in which Minoan palace society arose on Crete. It has also been shown that this rise was stimulated in part by the results of sea trade. These simultaneous events in Crete and Phoenicia might have been just a remarkable coincidence—were it not for the large quantity of additional evidence.

The written language of the Minoans, called ‘Linear A,’ was well known to have Semitic roots among its heritage.[xlix] The reason why this would have been the case was not clear in the past. But in the context of arriving Phoenicians, who were a Semitic-speaking people, it is quite reasonable.

As Evans discovered when he unearthed the first of the palaces at Knossos, those edifices included huge warehouses. Among the Phoenicians, the trading house and accompanying warehouses were essential to their existence. At Knossos, the north entrance to the palace has been clearly identified as a trading house or customs house.[l] Likewise, a major portion of the ‘palace’ behind it has been shown to consist of warehouses. It should be noted that—outside of Phoenician society—the use of a king’s residence as a trading house and warehouse was an extremely rare occurrence.

As previously mentioned, the Phoenician trading house served not only as the home of its king, but as the administrative center of the city. In addition, the king or a member of his family served as the highest-ranking person in their local religious order.[li],[lii] Among the Minoans, the palace served as a trading house, warehouse, administrative center, religious center, and residence for the king. The parallels between the two cultures are remarkably striking. I have been able to find no other societies which had this same assemblage.

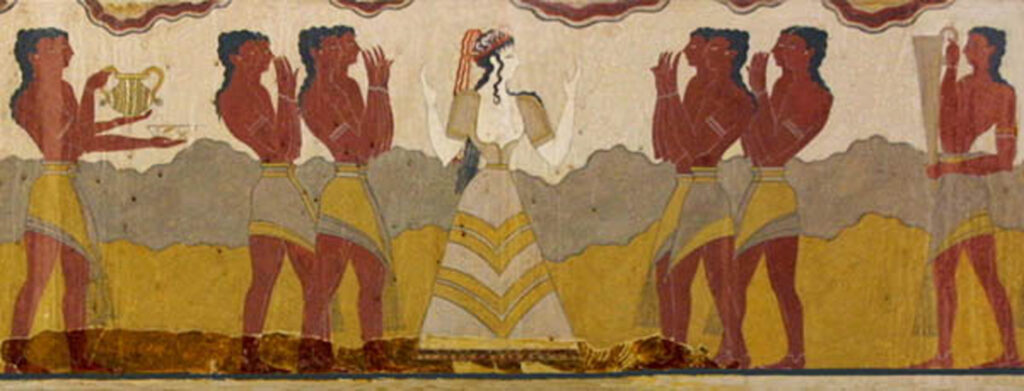

In addition, historians have often commented on the peacefulness of Minoan society. The ancient and beautiful Minoan wall paintings support this observation, since they have a surprising attribute unheard-of in most contemporary societies: they contain not a single picture of a soldier, nor even a stern-faced ruler. All the Minoan frescoes show happy, peaceful people enjoying a good life. The other extraordinarily peaceful society at this time belonged to the Phoenicians, who relied upon negotiation rather than fighting[liii] and, throughout their long history in Lebanon, had no army.[liv] This was highly unusual in the Mediterranean of that day, yet this remarkable peacefulness characterized both societies.

To look in another direction, a number of Egyptian objects and imitations of Egyptian design were found among the Minoans. What do we make of this? It is noted that the Phoenicians’ close trading relationship with the Egyptians has been well established.[lv] Given this link, it would have been unusual if Egyptian objects had not been found at Crete. The well-known ‘circle route’ of sea-trade in the Eastern Mediterranean linked Phoenicia, Crete and Egypt. Occasional passengers on those merchant ships may also have made the trip between these lands.

The Phoenicians were clearly bearers of Egyptian culture. As has been pointed out, the Phoenicians preferred to blend in with the powerful people around them, and not be singled out. They adopted surface elements of these other cultures, and even built temples in honor of these other peoples’ deities. This was especially true of their largest customer, the Egyptians.[lvi] So it is not surprising to discover elements of Egyptian dress, architecture and burials made their way to Crete from Egypt, as previously documented. Of course, the Egyptians were not the only customer of the Phoenicians. A smaller number of artifacts and cultural influences from the Phoenicians’ lesser trading partners in Anatolia and the Levant have also been found in Crete.[lvii] And again, occasional travelers between those lands could have made the journey.

In terms of seamanship, historians state that both the Minoans and the Phoenicians were the dominant traders on the seas at this time.[lviii],[lix] Yet there was not a single mention in the extensive Greek and Egyptian records of antiquity regarding any conflict or fights between the Minoan and Phoenician fleets. This stands in stark contrast to the Greeks’ forays upon the seas a thousand years later, when they sought to erode the Phoenicians’ dominance and establish their own trade and mastery of the seas. The latter competition and battles between Greeks and Phoenicians were legendary, and appeared in accounts of the Persian War, the Peloponnesian War, and the fight for control of Sicily.[lx] Of course, we now understand why the much earlier Minoans and Phoenicians did not fight each other. As we have seen, the arrival of Phoenicians in Crete seems to have given the Minoans a family relationship to the Phoenicians.

The end of this Minoan society left us with one more thing to consider. The massive volcano eruption at Santorini circa 1628 BC[lxi] was believed to have severely damaged the once-glittering Minoan society, as did other natural disasters in subsequent years. The death-blow came in LM IB (ca. 1500 – 1450 BC) when battle-ready Mycenaeans from the mainland swept over the weakened people of Crete. As Minoans fled before the invaders, where did they go?

The answer to that question came from an unexpected source. At Tyre and Sidon in Lebanon, excavations by Bikai and others revealed that at this time, circa 1425 BC, both cities became permanently repopulated.[lxii] They quickly grew into thriving Phoenician trade centers once more.

Chronology

A word is necessary about the various chronologies used by historians in discussing the events of these times. For a number of reasons archaeologists, historians and scientists cannot agree on a uniform set of dates for occurrences in the ancient Mediterranean. Even monumental events such as the massive volcano eruption on Santorini—which had a clear and profound effect on geology, archaeological sites, cultures and history—has not been assigned an agreed-upon date to within 100 years.[lxiii]

For the beginning of the palace-building period on Crete, which is designated MM IB, some use an early date of 2000 BC while others use a late date of 1900 BC. Most use the compromise date of 1950 BC. Similarly for the end of the Minoan palace society, and the beginning of the Mycenaean period on Crete, which is designated LM IB. The end of this period traditionally has an early date of 1550 BC and a late date of 1450 BC. Most often, a date between 1500 BC and 1450 BC is used for this event.[lxiv],[lxv],[lxvi],[lxvii],[lxviii],[lxix]

Realistically, the arrival of outsiders at Crete just prior to the palace-building period—and their impact upon the local society—would not have occurred in a single year. Initial contact, as shown above, appears to have lasted for 1000 years, and took the form of gradually increasing trade and prosperity. Even a period of heavy immigration near the year 2000 BC would reasonably have taken one or two generations to accomplish. In addition, given their demonstrated preference to blend in, the effect the Phoenicians had on the local society reasonably would have occurred over some period of time—perhaps fifty or one hundred years—before visible architectural and other changes were seen. At the present time, the most we can say is that the impact of the Phoenicians’ arrival at Crete in significant numbers, just before 2000 BC, would have been most strongly felt after 2000 BC.

Similarly with changes during the last days of Minoan society. The exact date of the Mycenaeans’ arrival on Crete is not known. And while the Mycenaeans no doubt moved quickly because there were no defensive walls nor Minoan army to hinder them, Crete was a large island with many mountains and valleys. People fleeing the oncoming forces, especially those people with strong Phoenician ties and no desire to stay and fight, would have quickly retreated to some safe place on Crete or another island, before continuing on to Tyre and Sidon in Lebanon. At this point the most which can be said is that the bulk of the arrivals at Tyre and Sidon occurred after 1425 BC, suggesting that the events which triggered this happened prior to that date.

Conclusions

To briefly sum up the results of the evidence examined here: With respect to Renfrew’s theory of indigenous development on Crete, extensive archaeological work turned up no evidence of widespread grape and olive production at the early date he required, which was a devastating blow. Then, with regard to the smooth upward sweep of development he hoped to find leading to the building of the Minoan palaces, Cherry and others found instead a ‘quantum leap’ at that critical time. The fallback position by van Andel and Runnels, which admitted there was outside trade but attempted to postulate this trade was limited to the Aegean, was likewise unsuccessful. Clear evidence of trade and influence from the East is much in view.

Further, we clearly saw Tyre and Sidon were essentially abandoned at the same time Minoan palace society came to life. Both the Minoans and the Phoenicians were renowned sea traders, and dominated the seas at the same time without any sign of fighting between them. Both societies mixed the roles of their trading house, king’s residence, and administrative center. Both societies were peaceful by nature, a highly unusual trait in those times of widespread armies and warfare. And when Minoan society finally fell, the Phoenician cities of Tyre and Sidon came to life again. There was no other people or society in the Mediterranean during those centuries which shared all these remarkable occurrences.

To take the opposite view—and claim this could just be a coincidence—might be effective against one of these elements. When the sum of all the elements are considered together, however, it leads to a compelling conclusion. The rise of Minoan palace society was clearly due to Eastern influence. Further, it is noted that the Eastern influence arrived on Crete in the form of the Phoenicians. Other influences arrived from Egypt and, to a lesser extent, from Anatolia and Mesopotamia.

On a larger stage, it is widely acknowledged today that the Minoans had a great influence upon the early Greeks. We now see how the Minoans received many of these influences from the Phoenicians, Egyptians and others.

Later, of course, other non-European influences would come directly to the classical Greeks. These included the Phoenicians’ bringing the alphabet to Greece, as acknowledged by Herodotus[lxx] and virtually all linguists around the world. The Greeks adapted this to their own use by adding vowels, and created a better alphabet. With it they wrote the great classical works of Socrates, Plato, Aeschylus, Euripides and many others.

The debt of Western civilization to the contributions of the Phoenicians, Egyptians and other non-Europeans is now much in evidence. It is time to acknowledge the contributions by many people to civilization as it exists in the world today. While the discussion here has been focused on the West, we should acknowledge all the peoples who contributed to the rise of civilization—in the East and in the West.

Notes

[i] Nilsson, Martin The Mycenaean Origin of Greek Mythology (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1972 [1932]).

[ii] Bernal, Martin Black Athena: The Afroasiatic Roots of Classical Civilization, Vol. II (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1991), p. 73.

[iii] Fitton, J. Lesley Minoans (London: British Museum Press, 2002), p. 6.

[iv] Rutter, Jeremy “The First Palaces in the Aegean” in Prehistoric Archaeology of the Aegean (http://projectsx.dartmouth.edu/history/bronze_age/lessons/les/11.html) Created 18 March 2000, retrieved 14 February 2006.

[v] Renfrew, Colin The Emergence of Civilisation: The Cyclades and the Aegean in the Third Millennium BC (London: Methuen, 1972), pp. xxv-547.

[vi] Rutter, Jeremy “The First Palaces in the Aegean” in Prehistoric Archaeology of the Aegean (http://projectsx.dartmouth.edu/history/bronze_age/lessons/les/11.html) Created 18 March 2000, retrieved 14 February 2006.

[vii] Bernal, Martin Black Athena: The Afroasiatic Roots of Classical Civilization, Vol. I (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1987), pp. 1-2.

[viii] Lefkowitz, Mary and Guy Rogers, eds., Black Athena Revisited (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina, 1996), pp. 3-454.

[ix] Rutter, Jeremy “The First Palaces in the Aegean” in Prehistoric Archaeology of the Aegean (http://projectsx.dartmouth.edu/history/bronze_age/lessons/les/11.html) Created 18 March 2000, retrieved 14 February 2006.

[x] Renfrew, Colin The Emergence of Civilisation: The Cyclades and the Aegean in the Third Millennium BC (London: Methuen, 1972), pp. xxv-547.

[xi] Rutter, Jeremy “The First Palaces in the Aegean” in Prehistoric Archaeology of the Aegean (http://projectsx.dartmouth.edu/history/bronze_age/lessons/les/11.html) Created 18 March 2000, retrieved 14 February 2006.

[xii] Gamble, Clive “Surplus and Self-Sufficiency in the Cycladic Subsistence Economy,” in J. L. Davis and J. F. Cherry (eds.), Papers in Cycladic Prehistory (Los Angeles 1979), pp. 122-134.

[xiii] Halstead, Paul “From Determinism to Uncertainty: Social Storage and the Rise of the Minoan Palace,” in A. Sheridan and G. Bailey (eds.), Economic Archaeology (Oxford 1981), pp. 187-213.

[xiv] Grant, Michael The Ancient Mediterranean (New York: Meridian, 1988), pp. 41-2.

[xv] Van Andel, Tjeerd and Curtis Runnels “An Essay on the ‘Emergence of Civilization’ in the Aegean World,” Antiquity 62(1988), pp. 234-247.

[xvi] Rutter, Jeremy “The Early Minoan Period: The Settlements” in Prehistoric Archaeology of the Aegean (http://projectsx.dartmouth.edu/history/bronze_age/lessons/les/5.html) Created 18 March 2000, retrieved 14 February 2006.

[xvii] Fitton, J. Lesley Minoans (London: British Museum Press, 2002), pp. 23-4.

[xviii] Rutter, Jeremy “The Early Minoan Period: The Settlements” in Prehistoric Archaeology of the Aegean (http://projectsx.dartmouth.edu/history/bronze_age/lessons/les/5.html) Created 18 March 2000, retrieved 14 February 2006.

[xix] Ward, W.A. Egypt and the East Mediterranean World 2200 – 1900 BC: Studies in Egyptian Foreign Relations During the First Intermediate Period (Beirut: American University of Beirut, 1971), pp. 92-5.

[xx] Rutter, Jeremy “Middle Minoan Crete” in Prehistoric Archaeology of the Aegean (http://projectsx.dartmouth.edu/history/bronze_age/lessons/les/10.html) Created 18 March 2000, retrieved 14 February 2006.

[xxi] Renfrew, Colin The Emergence of Civilisation: The Cyclades and the Aegean in the Third Millennium BC (London: Methuen, 1972), pp. 269, 281.

[xxii] Branigan, Keith The Foundations of Palatial Crete (London: Duckworth, 1970), pp.199-200.

[xxiii] Weinberg, Saul “The relative chronology of the Aegean in the Neolithic period and the Early Bronze Age,” in R.W. Ehrich, ed., Relative Chronologies in Old World Archaeology (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1954), p. 95.

[xxiv] Weinberg, Saul “The relative chronology of the Aegean in the Neolithic period and the Early Bronze Age,” in R.W. Ehrich, ed., Relative Chronologies in Old World Archaeology (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1965), pp. 302-8.

[xxv] Branigan, Keith The Foundations of Palatial Crete (London: Duckworth, 1970), pp.199-203.

[xxvi] Holst, Sanford Phoenicians: Lebanon’s Epic Heritage (Los Angeles: Cambridge & Boston Press, 2005), pp. 26-32.

[xxvii] Branigan, Keith The Foundations of Palatial Crete (London: Duckworth, 1970), p.81.

[xxviii] Rutter, Jeremy “Middle Minoan Crete” in Prehistoric Archaeology of the Aegean (http://projectsx.dartmouth.edu/history/bronze_age/lessons/les/10.html) Created 18 March 2000, retrieved 14 February 2006.

[xxix] Watrous, L. Vance “Egypt and Crete in the Early Middle Bronze Age: A Case of Trade and Cultural Diffusion,” in E. H. Cline and D. Harris-Cline, eds., The Aegean and the Orient in the Second Millennium [Aegaeum 18] (Liège/Austin 1998), p. 24.

[xxx] Cherry, John “Evolution, Revolution, and the Origins of Complex Society in Minoan Crete,” in O. Krzyszkowska and L. Nixon, eds., Minoan Society (Bristol: Bristol Classical Press, 1983), p. 33.

[xxxi] Bernal, Martin Black Athena: The Afroasiatic Roots of Classical Civilization, Vol. II (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1991), p. 154.

[xxxii] Bernal, Martin Black Athena: The Afroasiatic Roots of Classical Civilization, Vol. II (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1991), p. 159.

[xxxiii] Watrous, L. Vance “The Role of the Near East in the Rise of the Cretan Palaces,” in R. Hägg and N. Marinatos, eds., The Function of the Minoan Palaces (Stockholm 1987), p. 67.

[xxxiv] Graham, James Walter The Palaces of Crete (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1962), pp. 231-2.

[xxxv] Davies, Vivian and Renee Friedman Egypt Uncovered (New York: Stewart, Tabori & Chang, 1998), pp. 27-8.

[xxxvi] Bernal, Martin Black Athena: The Afroasiatic Roots of Classical Civilization, Vol. II (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1991), p. 70. Here is noted only the shift from north to south in the Aegean.

[xxxvii] Herodotus The Histories Robin Waterfield, trans. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998), 2:44.

[xxxviii] Bikai, Patricia The Pottery of Tyre (Warminster, UK: Aris & Phillips, 1978), p. 72.

[xxxix] British Museum “Seasons 98,00,01” in Sidon Excavation (http://www.sidonexcavation.org/9800/sea98-00.html) Retrieved 15 April 2006).

[xl] Bentley, Jerry and Herbert Ziegler Traditions & Encounters (New York: McGraw Hill, 2000), p. 51.

[xli] Lichtheim, Miriam Ancient Egyptian Literature: Volume II: The New Kingdom (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1976), pp. 224-9.

[xlii] Holst, Sanford Phoenicians: Lebanon’s Epic Heritage (Los Angeles: Cambridge & Boston Press, 2005), pp. 59-61.

[xliii] Markoe, Glenn Peoples of the Past: Phoenicians (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000), pp. 10-13.

[xliv] Holst, Sanford Phoenicians: Lebanon’s Epic Heritage (Los Angeles: Cambridge & Boston Press, 2005).

[xlv] Dunand, Maurice Byblos H. Tabet, trans (Paris: Librairie Adrien-Maisonneuve, 1973) pp. 22-3.

[xlvi] Bikai, Patricia The Pottery of Tyre (Warminster, UK: Aris & Phillips, 1978), p. 72.

[xlvii] British Museum “Season 01” in Sidon Excavation (http://www.sidonexcavation.org/2001/sea2001.html) Retrieved 15 April 2006).

[xlviii] Dunand, Maurice Byblos H. Tabet, trans (Paris: Librairie Adrien-Maisonneuve, 1973) pp. 22-3.

[xlix] Bernal, Martin Black Athena: The Afroasiatic Roots of Classical Civilization, Vol. I (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1987), p. 417.

[l] Poffley, Frewin Greek Island Hopping (Peterborough, UK: Thomas Cook Publishing, 2004), pp. 305-6.

[li] Markoe, Glenn Peoples of the Past: Phoenicians (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000), p. 120.

[lii] Holst, Sanford Phoenicians: Lebanon’s Epic Heritage (Los Angeles: Cambridge & Boston Press, 2005), p. 135.

[liii] Markoe, Glenn Peoples of the Past: Phoenicians (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000), pp. 34,39.

[liv] Holst, Sanford Phoenicians: Lebanon’s Epic Heritage (Los Angeles: Cambridge & Boston Press, 2005), p. 62.

[lv] Watrous, L. Vance “Egypt and Crete in the Early Middle Bronze Age: A Case of Trade and Cultural Diffusion,” in E. H. Cline and D. Harris-Cline, eds., The Aegean and the Orient in the Second Millennium [Aegaeum 18] (Liège/Austin 1998), pp. 19-20.

[lvi] Dunand, Maurice Byblos H. Tabet, trans (Paris: Librairie Adrien-Maisonneuve, 1973) p. 54.

[lvii] Rutter, Jeremy “Middle Minoan Crete” in Prehistoric Archaeology of the Aegean (http://projectsx.dartmouth.edu/history/bronze_age/lessons/les/10.html) Created 18 March 2000, retrieved 14 February 2006.

[lviii] Thucydides History of the Peloponnesian War Rex Warner, trans. (New York: Penguin, 1972), 1:4-8.

[lix] Bentley, Jerry and Herbert Ziegler Traditions & Encounters (New York: McGraw Hill, 2000), p. 51.

[lx] Thucydides History of the Peloponnesian War Rex Warner, trans. (New York: Penguin, 1972), 1:16.

[lxi] Manning, Sturt A Test of Time: The Volcano of Thera and the Chronology and History of the Aegean and East Mediterranean in the Mid Second Millennium BC (Oxford: Oxbow Books, 1999), pp. 1-419.

[lxii] Bikai, Patricia The Pottery of Tyre (Warminster, UK: Aris & Phillips, 1978), p. 65. It should be noted that “visits” preceded this permanent resettlement at Tyre, beginning in 1600 BC just after the volcano eruption at Santorini.

[lxiii] Manning, Sturt A Test of Time: The Volcano of Thera and the Chronology and History of the Aegean and East Mediterranean in the Mid Second Millennium BC (Oxford: Oxbow Books, 1999), p. 3.

[lxiv] Boardman, John et al, eds., Cambridge Ancient History (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991).

[lxv] Kemp, B.J. and R.S. Merrillees Minoan Pottery in Second Millennium Egypt. Deutches archäologisches institut, Abteilung Kairo. (Mainz am Rhein: Philipp von Zabern, 1980).

[lxvi] Betancourt, P.P. “High chronology and low chronology: Thera archaeological evidence” in Thera and the Aegean World III: Papers to Be Presented at the Third International Congress at Santorini, Greece, 3-9 September 1989. Thera Foundation, pp. 9-17.

[lxvii] Bernal, Martin Black Athena: The Afroasiatic Roots of Classical Civilization, Vol. II (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1991), p. xxxiii.

[lxviii] Rutter, Jeremy “Chronology and Terminology” in Prehistoric Archaeology of the Aegean (http://projectsx.dartmouth.edu/history/bronze_age/chrono.html) Created 30 December 2005, retrieved 14 February 2006.

[lxix] Fitton, J. Lesley Minoans (London: British Museum Press, 2002), pp. 6-7.

[lxx] Herodotus The Histories Robin Waterfield, trans. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998), 5:58.

Further information

If you would like to experience more of the Phoenician world than you found in this article, the book Phoenicians: Lebanon’s Epic Heritage is recommended. It is deeply researched but also a highly readable exploration, with 104 illustrations.

Going beyond the few traditionally-cited facts, this authoritative work also draws from interviews with leading archaeologists and historians on-site in the lands and islands where the Phoenicians lived and left clues regarding their secretive society.

Phoenicians

You can take a look inside this book. See the first pages here.